Records are part of the Java language since version 14. They are a useful feature for types that primarily capture data and avoid some of the boilerplate that Java is famous for. While many traditional class hierarchies could be translated to records, I found the discussion around which of them should be adapted to that style quite controversial.

In this piece, I want to first look at a number of uncontroversial uses of records and then discuss some of the more controversial ones.

Simple Value Classes

The canonical use case for records is an entity that mainly represents data. Traditionally you might want to model a user class as follows:

public final class User {

private final String firstName;

private final String lastName;

private final int age;

public User(String firstName, String lastName, int age) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.age = age;

}

public String firstName() {

return this.firstName;

}

public String lastName() {

return this.lastName;

}

public String age() {

return this.age;

}

@Override

public boolean equals(Object other) {

// ...

}

@Override

public long hashCode() {

// ...

}

}

This is exactly the use case records are designed for. The equivalent code using a record has the same behavior with much less boilerplate:

public record User(String firstName, String lastName, int age) {}

The result of this definition is the same as the definition above: A immutable value-class that contains exactly the data set in the constructor. Classes that represent immutable data are quite common – often they can be derived quite naturally from the problem domain of a program.

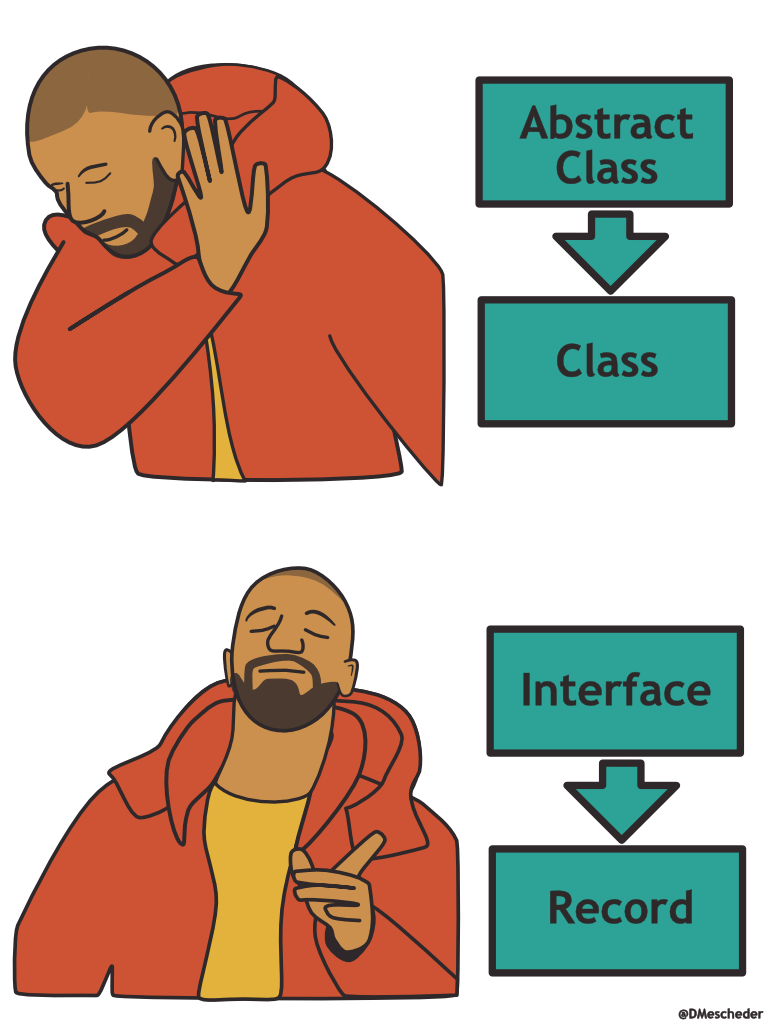

Implementing Interfaces

Records are final which means it is not possible to create a class that inherits from a record type. However, that does not mean it is impossible to create type hierarchies with records: The alternative design is to use interfaces for the inner nodes of the type hierarchy and records for the leaves which provide the implementation.

For this is it useful to observe that the autogenerated getters can implement interface functions:

public interface HasAge {

int age();

}

public record User(String firstName, String lastName, int age) implements HasAge {}

This enables polymorphism and the succinctness and immutable-by-default semantics of records. Another way that “hierarchies” can be built up using records is by favoring composition over inheritance which some people argue should be the default anyway.

A Projection In jOOQ

So records are designed for data classes. What are those anyway? What about the data returned by a Jooq query for example which corresponds to the type of a given table row. That still sounds like an example of data!

Indeed, records can be used out of the box with jOOQ as the result of a projection can be mapped to a java class as long as the order of columns in the projection matches the order of arguments in the constructor. Using the same record shown above, we can thus write a query like the following:

List<User> users= dslContext

.select(USER.FIRST_NAME, USER.LAST_NAME, USER.AGE)

.from(USER)

.fetchInto(User.class);

The same could be achieved with a plain old Java class, of course – however, it is neat to know that records can be used as a DTO, eliminating much of the typical boilerplate.

A Configuration Record in Spring Boot

ConfigurationProperties classes in Spring Boot contain the definitions of the configuration with which your application is started. They look a bit like “DTOs” for your config files. As such, they do smell a bit like the “pure data” objects we considered above. Could we use records to model Spring configuration models and get around some of the boilerplate associated with that?

Absolutely!

@Configuration

@ConfigurationProperties(prefix = "smtpServer")

@ConstructorBinding

public record SmtpConfigProperties (String host, int port) {}

The important line here is the @ConstructorBinding annotation. Without this annotation, spring boot will try to use a default constructor and fill the data using setters. As a record is by definition immutable, this strategy will not work. Therefore, if we want to use records here, we will need to instruct Spring to inject the configuration properties using the constructor.

Other Final-By-Default Classes

Now we are getting into more controversial territory. Why stay limited to data-only classes? After all, we can add regular methods to record types. Why not simply replace all classes with records?

The main pushback that I have seen raised is that this is not what records have been designed for. Fair enough! However, I do see some arguments why using records by default may be a worthwhile consideration:

For one, they reduce the overall boilerplate required. I’m not too worried about the amount of code we need to type – IDEs have good autogeneration capabilities. However, I think that when reading code, boilerplate is a distraction from the thing that the code really tries to do.

Secondly, the default record hashCode and equals implementation make sense for most classes. This means that when you see a record with a custom definition for equals, there might be something to watch out for.

Most importantly, this encourages final-by-default code and immutable designs. It is easier to pass the same object into multiple threads if you don’t need to worry about one of these threads mutating the object in unexpected ways.

Making record the default means that some common Java patterns will not work – which is maybe not appropriate for all situations. On the other hand, the class primitive is still available for those situations where it matters.

Other situations that require mutations can typically be translated into immutable code with varying overhead:

public final class Car {

private final int totalDrivenDistance;

// ... other boilerplate ...

public void drive(int newDistance) {

this.totalDrivenDistance = this.totalDrivenDistance + newDistance;

}

}

Could be replaced by an immutable version as follows:

public record Car(int totalDrivenDistance) {

public Car drive(int newDistance) {

return new Car(this.totalDrivenDistance() + newDistance);

}

}

Instead of mutating the state of an object, we can always choose to create a new object with the updated state. Using this style, of course, also requires changes in the code using this class. For example, you can no longer return data to the caller of a function by mutating an input parameter. Instead, you would have to create and return a new object. This comes with some overhead – but I would also argue that this results in fewer surprises, especially when operating on multiple threads that access shared memory.

Mocking a Record With Mockito

When records are used as data classes, it is often preferable to simply instantiate an object rather than mocking it. However, when we start using records in other areas, it may become necessary to mock their behavior. By default, Mockito relies on inheritance for mocking, leading to a problem with records as they are final.

There is an easy fix for that: By configuring Mockito to use mock-maker-inline as described here, mocking will work as expected on final classes – and this includes records.

Spring Components

The most controversial take I have seen is the use of records for Spring components. Would it not be tempting to use them, just to get rid of some of the typical boilerplate? As Spring can autowire dependencies through the constructor, the following does technically work:

@Service

public record UserService(UserRepository userRepository) {

public List<User> findUserByName(String name) {

// ...

return userRepository.findUserByName(name);

}

}

Some of the points raised above about using records beyond value classes apply. Though, it must be said that equals, hashCodes, and getter methods (all generated by the record) are not typically useful on service classes, limiting the use of records in this context.

Personally, I am still on the fence about this use. I do see that this is stretching records far beyond their original goal. However, I like the way that this pattern discourages creating and updating mutable fields inside your service class.

Conclusion

With records, Java has learned from the successes of some of the JVM competitors like Scala and Kotlin that provide patterns with a much smaller boilerplate footprint than your typical Java class. While it can be debated, how far exactly we should take this pattern, I would argue that at least for modeling your problem domain they do prove their worth. Personally, I am not completely against pushing the boundaries as a means of forcing programmers to consider solutions that avoid mutable state.

Leave a comment