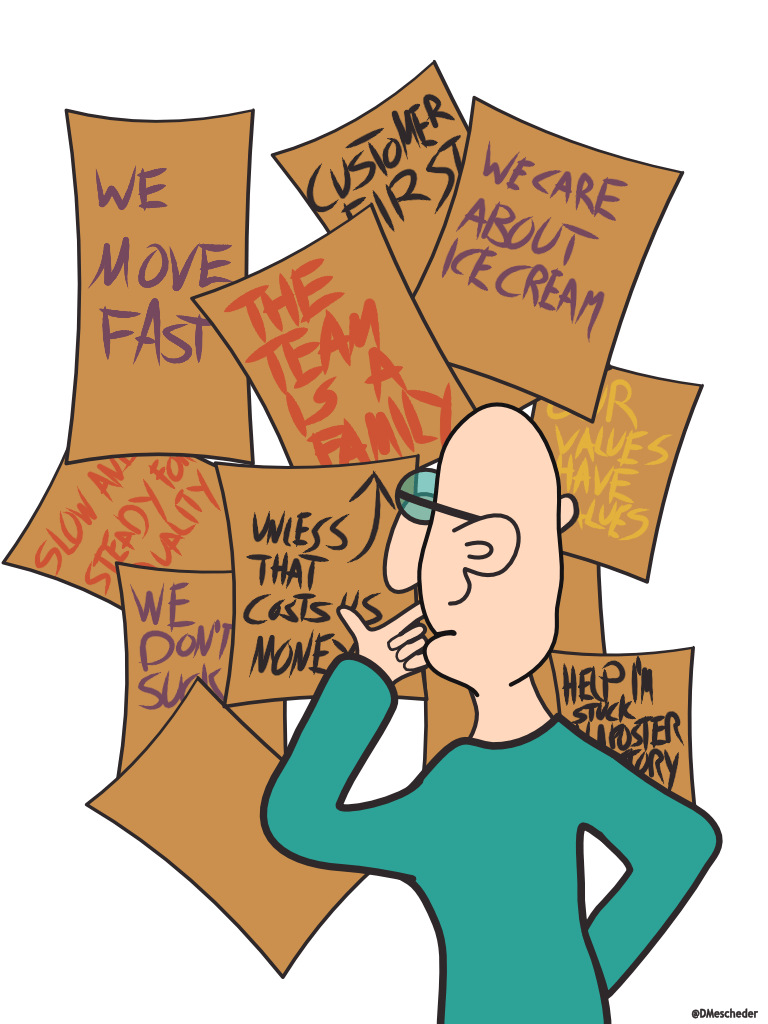

Senior leadership did the analysis: The root of the problem at XYZ Corp was a lack of clearly defined value statements that underpin the company’s unique culture! Problems like this demand the corporate weapon of choice to jump into action: The Workgroup. The Workgroup started to flesh out a series of carefully crafted statements that should form the lifeblood to revitalize XYZ Corp (they made sure to get some help from BainKinsey Group to get the messaging just right!). As one of the values of XYZ Corp would be a data-driven culture, a scientific experiment was run: Two subsamples of employees were asked to rate different statements on a scale from one to ten. This data was then used in the final phase of the process: The Executive Tug Of War! Based on The Data and the stories told of the great culture over at Apmasoft and Spotifix, the executives negotiated a set of statements that seemed fitting (and that, no doubt, carefully avoided threatening any one of the executives’ turfs). The big day was finally there: A branding and design agency had been tasked with the production of posters and slides, an all-hands was called, and, with great fanfare, the CEO rolled out what would become the foundation of XYZ Corp 2.0. As the all-hands dragged on, Eric, a senior engineer in the audience, started to get a bit nervous: “Sure, it is nice we will get some new wall decor” he thought to himself, “but when can I finally get back to my project which is due on Thursday?”

I find exercises like this to be one of the great sources of corporate comedy. So, does this prove that company values are just vacuous business theater or can they be useful? In this article, I want to argue that they can be of value and I want to discuss why. I would also like to propose a simple test based on where I have personally benefited from such statements (and where less so).

I see two big categories of problems with company values. The biggest elephant in the room is the gap between the values stated on paper and the values lived. Your company states “We care about the environment” and people that undertake projects in that direction are systematically kept down in small niches while that guy that proposed the Let’s-Dump-Our-Waste-Into-The-River strategy is collecting promotions? Clearly, the revealed preferences of the organization contradict the stated values. If the company says “We are family” and then goes on to throw the lowest performers under the bus once the economic climate changes, this signals of a similar discrepancy – though, who knows, maybe the CEO’s family is a pretty cut-throat environment, too.

Before considering this obvious challenge, I want to consider the second problem first: Whether or not the phrasing of company values is helpful when making a decision.

Values Must Help In Decision Making

The problem with many company values is that they are vague, self-evident, or contradictory. For instance, phrases like “we value integrity,” “we are innovative,” and “we strive for excellence” may sound good, but do they help employees navigate real-world situations?

The main way in which company values can be useful is in decentralizing decision-making. Employees need to make judgment calls all the time: Do I spend some extra time to polish this code or do I push it out as soon as possible? Do I prioritize helping out the junior who is struggling or answering an incoming customer request? Should I take the initiative to fix this problem that is not strictly speaking my job or should I escalate this up to get the responsible team to have a look?

Having guiding principles can help employees make such decisions autonomously without having to refer back to management all the time. Therefore, guiding principles that encourage decentralized decision-making decrease overhead and improve efficiency.

This directly leads us to a test to determine if a set of values is useful: They should help an individual in deciding which action to favor. To this end, the first values you should eliminate are those that are self-evident. A good test for a self-evident value is if it can be reversed and still provide useful guidance. “We have fun at work” is an example. What should a workplace that takes the opposite bet write on its posters? “We despise Mondays”? What is the opposite value of “we act with integrity”? “We cheat our way to the top”? “Teamwork” is also a self-evident value. Of course, everyone wants you to work with your team!

Furthermore, values need a hierarchy. If you state both “the customer comes first” and “we care about each other”, it needs to be clear, which one of the two takes precedence if in doubt. Should I push the change that the customer is waiting for on Friday evening, knowing that this could lead to our on-call getting paged over the weekend? Who is more important, my colleague or the customer?

The value also needs to be as concrete as possible and ideally provide examples. Is “we care about quality” a valid reason to fine-tune the performance of my API for another six months? What does quality mean in this context? Does “be innovative” mean that it is okay for me to spend several days on that weird idea I had, rather than the feature the customer is waiting for?

Values that are useful can serve as guidelines. “Be innovative” can be somewhat useful: It provides an argument for employees to try something new rather than replicating what is already known to work. Importantly, however, being innovative always comes with a risk of failure. So the next value on the list must not be something contradictory like “we succeed in all we undertake”. “Customer focus” is valuable and very actionable, provided it is defined clearly and consistently. It provides the guidance that if in doubt, it is better to spend some extra time to help the customer rather than, say, work on operational efficiency.

We have seen that values are really only useful if there is some trade-off to navigate. Take the value “diversity” as an example. This value can be useful and guide behavior: If I’m hesitating between a candidate that seems slightly more qualified and one who would increase the diversity on the team along the dimensions you care about, this value gives permission to pass on the former and prefer the latter. If a candidate matches all criteria, the choice would have been obvious and does not require any guiding principles. Conversely, if you don’t want me to pass on a seemingly more qualified candidate in favor of increased diversity and you don’t feel comfortable undertaking disciplinary steps against a top performer who makes minority team members feel unwelcome, this should probably not be a stated value.

Values Must Be Coherent With Strategy

This brings us to the second big challenge: Of course, the usefulness of company values depends not only on their content but also on how they are reinforced. Simply listing values on a website or a poster is not enough. They must be reflected in the company’s practices. Values must be reinforced through actions, providing employees examples of how to apply them in real-world situations.

If your stated goal is to “move fast and break stuff” but in reality, teams are stuck in a bureaucratic quagmire, the value statement is not just useless but undermines the credibility of the entire enterprise.

The only way in which people have a chance to align themselves with company values is if these values are aligned with the strategy. If the goal is to be known as a reliable brand, “excellence” and “quality” can make it into the value statement. If the goal instead is to be the innovative disruptor, the same can be harmful. Faced with a break neck delivery timeline, individuals will find themselves in a dilemma between the de-facto expectations and the theoretical value statement.

How will you know that your values match reality? Here is a potential mechanism: Distribute anonymous surveys in which employees rank each other based on how well a person represents each company’s value. Importantly, the results would not be reported by individual but aggregated by job level. Everyone should be aware of this to remove a typical source of bias present in corporate surveys. You would expect that individuals further up the pyramid would represent values particularly well. Instead of being a framework to evaluate individuals, this gives a pointer where values might not match the reality of hiring and promotions. If you find a mismatch, it is maybe time, to be honest and revisit that value. You could also measure and aggregate over the standard distribution of the scores an individual receives for a given value. A large spread indicates that it is not directly obvious to people what behavior is implied by the value.

In summary, corporate values exercises receive a lot of ridicule. They can be useful to facilitate decentralized decision-making. To be useful, it is important they reflect the actual needs and strategy of the organization and form a coherent set of guidelines that can be used to navigate trade offs.

Leave a comment