Most people perceive salary negotiation as an unpleasant activity. One particular issue with the salary negotiation process that has been observed is, that candidates unable to approach a negotiation from a position of strength are at a disadvantage.

While I am not sure by how much this moves the needle against people already in a disadvantaged position, it appears intuitive that candidates that can fall back on a comfortable economic cushion in case of a failed negotiation can more credibly threaten to walk away from the table.

In this article, I want to propose an alternative mechanism that levels the playing field by moving the salary negotiation to a third party.

According to the argument of critics, the behavioural component of the negotiation process, prevents prices from achieving their equilibrium and creates a bias towards those that feel comfortable rejecting an offer simply because of their privileged situation.

I do not have any data to prove or disprove this argument. It does in any case sound plausible. Could we organised salary negotiations in a way that eliminated this bias?

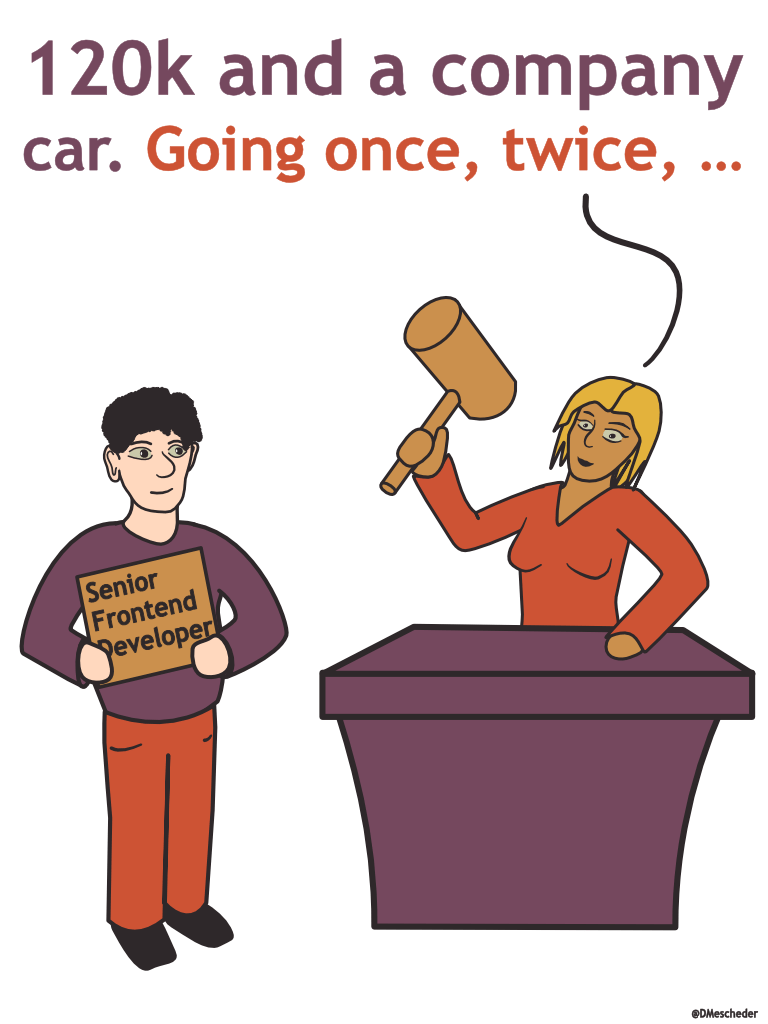

What I am proposing in this article is to bring a third party into the picture that acts like a match maker between sellers (job seekers) and buyers (employers). Think of it like an auction house. Recruiting agencies are already present in this space. However, their mission does not typically include establishing a fair market price for candidates.

Imagine a job hunting process that works as follows: As a first step, a candidate opens an account on a platform of such a provider, selecting a target date by when they aim to make a choice. Let us say two months from now. With that account open they go out and interview at five different companies.

At the end of the interviewing process, instead of extending an offer directly to the candidate, an interested employer would enter their bid into the system.

The candidate should probably be notified about the number of companies that were interested enough to make an offer in order to know how much energy they need to spend on trying to get more offers.

When the deadline set by the candidate at the start of the process expires, the system will reveal to the candidate the companies willing to make an offer and the respective compensation. However, the highest bidder will have their offer capped at the bid of the second highest bidder.

It is this feature that would make the system incentive compatible: A prospective employer is incentivised to bid the real value they think the candidate could contribute rather than strategically aiming below that value.

In the easiest scenario, the candidate would accept the highest bidder at the second-highest price and a fair match has been made.

(For those interested, such a procedure is also known as a Vickrey auction.)

Can the candidate select from non-winning offers?

A candidate might value different offers differently, irrespective of their monetary value. They may have a preference for a brand, a particular type of work, or account for other non-monetary factors like an employer’s remote working policy. A naive implementation allowing for non-monetary preferences would be to allow the candidate to select a bid other than the winning bid at the end of the procedure.

A downside of this is that introducing such a choice allows the candidate to game the system: They could ask a friend to place an extremely high bid, promising to not accept the friend’s offer. That way, all other bids are necessarily pushed to their maximum.

From the employer’s perspective, knowing that the system can be gamed breaks the incentive compatibility of the mechanism meaning that employers may have an incentive to strategically discount their bids.

Another idea to implement non-monetary preferences would be to allow the candidate to set a separate reserve price for each potential employer. This procedure suffers from the same problem described above (you could arrange a reserve price that is always higher than your friend’s bid) but also features some additional challenges that I will dive into below.

With these points in mind, an alternative would be the following: Let the candidate rule out beforehand any prospective employers that rank low in their non-monetary preferences. In the remaining pool, the candidate commits to accepting the highest bidder. An employer that has been eliminated cannot raise the price cap with their offer.

This is also not ideal as it does not provide a way of expressing that “I would never work for company X unless they pay me a lot”. Also, automatically accepting the highest bidder could be seen as a loss of agency on the candidate’s side as they might keep less desirable prospective employers in the pool to make sure they get a good deal without any way of refusing an undesirable outcome later.

I suppose there could be regulatory steps that the central party could take to rule out candidates gaming the system as outlined above. This problem definitely requires more thought.

Can the candidate set a reserve price?

Reserve prices are a way for the candidate to set minimums on any offer they are willing to consider. I outlined one use case for reserve prices above as a way of expressing non-monetary preferences.

However, there is a big problem with reserve prices in this context: They are a way for the candidate to threaten to walk away from the table by setting their minimum requirements high. This re-introduces the problem that we originally set out to solve: A candidate in a privileged position could set a high reserve price to maximise their outcomes. Therefore, to solve the original problem, reserve prices should probably be fixed globally, for example to a national minimum wage.

How does the current employer play into this system?

How does a candidate’s current employment factor into this procedure? One way of looking at this is that the current compensation forms a lower bound on the clearing price. This could be a solution to the reserve price problem discussed above: If a candidate can provide proof of their current compensation to the third party, this could be set as a natural reserve price without allowing strategic price setting by the candidate.

This would be optional: If a candidate is trying to get away from their current employer and willing to risk a pay cut, they could skip this step.

A more radical approach would be to invite the candidate’s current employer to participate in the system and coupling the yearly reassessment of the employee’s compensation to the outcome. This would have the benefit of lifting the common wisdom that big jumps in compensation necessarily require changing the employer.

However, I don’t think such a system would be accepted. There would be too many undesirable consequences: An employee hoping for a raise would need to be interviewing on a regular basis which comes with a significant time investment. Furthermore, this system could lead to an employee’s salary to go down, even if their current employer is willing to pay them more.

Other Challenges

Next to the points discussed above, this procedure has a number of other major challenges. Some of them I consider surmountable, but others I’m not so sure. Let us go through a number of problems:

Firstly, the mechanism relies on the assumption that offers are always directly comparable. In practice this is not the case: One company might offer equity, another offers more cash and a third provides a lot of extralegal benefits. How could these offers be compared? There would need to be a formula or mechanism that rolls up any offer into a comparable number. Not an easy task, especially if this includes assessing the value of pre-IPO startup options.

Secondly, for this mechanism to work as designed, a candidate would need multiple bids. However, there may be many reasons different from the candidate’s desirability to the market why a candidate can only get one offer at a given time. Maybe they have limited time for job hunting. Maybe they did not get lucky in the current round. An easy fix would be for the candidate to be able to skip the current round and to keep searching. However this would again benefit those candidates that are in a privileged position.

Thirdly, there are a number of challenges from the employer’s perspective: Typically, a company has one position to fill and needs to make a choice. If a candidate does not accept their offer, they might want to get back to a different candidate. In the proposed system, they cannot place a bid for two different candidates because they would not have the budget to hire both. In other words, the value they place on candidate A depends on whether or not they have a match with candidate B.

Big companies can potentially compensate by batching multiple open positions together, for smaller companies this seems more challenging.

There are auction mechanisms that allow placing more complex bids such as “I’m willing to pay EUR X for candidate A assuming I do not also get candidate B”. However, there we are getting into the territory of combinatorial auctions which come with significantly higher complexity.

With all of this, any person trying to implement this system would have to find convincing added value for a company to participate in this scheme.

Conclusion

There are many challenges and valid concerns with such a system and I think anyone attempting to implement it will face significant adoption hurdles. I do think, however, that if these challenges can be overcome that there might be a lot of value for all sides by making the market more efficient and taking the element of compensation-poker out of the hiring process.

An easier modification to your initial proposal, which still prevents gaming by candidates, would be to let them iteratively eliminate the top offer but at the cost of bumping the compensation down to the new 2nd-place offer.

That’s a nice idea, thanks for sharing!